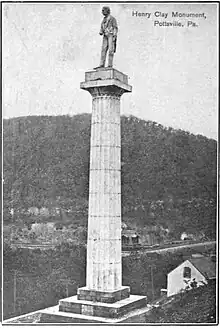

The monument, c. 1910 | |

| 40°40′53″N 76°11′33.5″W / 40.68139°N 76.192639°W | |

| Location | South Centre Street near Washington Street, Pottsville, Pennsylvania, United States |

|---|---|

| Designer | Frank Hewson (architect) H. Wesche (sculptor) Jacob Madara (stonemason) |

| Fabricator | George B. Fissler (column) Robert Wood & Company (statue) |

| Type | Doric column Statue |

| Material | Cast iron |

| Length | 15 feet (4.6 m) |

| Width | 6 feet (1.8 m) |

| Height | 67 feet (20 m) |

| Weight | 45.5 short tons (41.3 t) |

| Beginning date | July 26, 1852 |

| Completion date | June 27, 1855 |

| Dedicated date | July 4, 1855 Rededicated October 19, 1985 |

| Restored date | August 26, 1985 |

| Dedicated to | Henry Clay |

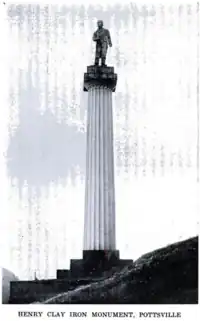

The Henry Clay Monument is a public monument in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, United States. Work on the monument, which consists of a state of Henry Clay atop a Doric column, began in 1852, shortly after his death, and ended in 1855.

As a politician in the early 19th century, Clay was an advocate for the American System of protective tariffs that helped Pottsville's anthracite industry, and upon his death in 1852, several prominent citizens in the city advocated for the erection of a monument in his honor. Work commenced with the laying of a cornerstone on July 26, 1852, and ended in June 1855, with the structure dedicated on July 4 (Independence Day) of that year. The column was designed by Frank Hewson and created by George Fissler, while the statue was designed by sculptor H. Wesche and cast at the Robert Wood & Company foundry in Philadelphia. Both these structures are made of cast iron and painted white.

Design

The monument consists of a column of the Doric order topped by a statue of Henry Clay,[1][2][3][4][5] similar in overall design to the Robert E. Lee Monument in New Orleans and Nelson's Column in London.[6][7] Both the column and the statue are made of cast iron,[4][5] and the entire structure is painted white.[2][1] The column rests on a stone base,[4] with materials quarried from nearby mountains.[8] The statue, which weighs about 7 short tons (6.4 t),[9][10] depicts a standing Clay whose appearance is based on the painting Senate of 1850 by Peter F. Rothermel.[3] Clay faces northwards, looking over the city.[9] The column is made up of eight segments, each 5 feet 3 inches (1.60 m) tall that are secured together by interior flanges.[8] The entire weight of both the column and the statue is roughly 45.5 short tons (41.3 t).[8]

The monument's base has a height of 4 feet (1.2 m) and an area of 15 feet (4.6 m) by 6 feet (1.8 m).[11] The column is 48 feet (15 m) tall, with a base covering an area of 8 feet (2.4 m) by 4 feet (1.2 m), while the statue is roughly 15 feet (4.6 m).[11][note 1] The monument is located on South Centre Street, near Washington Street,[11] on a ridge overlooking the city,[15][16] just beneath Cloud Home.[17] The base of the monument is situated about 133 feet (41 m) above the nearest sidewalk.[4]

The base of the monument has three inscriptions on its east, north, and south faces, which are as follows:[11]

IN HONOR OF HENRY CLAY. / THIS MONUMENT IS ERECTED / BY THE CITIZENS OF SCHUYLKILL COUNTY / AND BEQUEATHED TO THEIR CHILDREN. / A RECORD OF GRATITUDE / FOR HIS ILLUSTRIOUS SERVICES WHICH BROUGHT / PEACE, PROSPERITY AND GLORY TO HIS COUNTRY. / A TRIBUTE OF ADMIRATION / FOR THE VIRTUES WHICH ADORNED A USEFUL LIFE, AND WON FOR HIS IMPERISHABLE NAME THE / RESPECT AND AFFECTION OF MANKIND.

— East face

JOHN BANNAN ESQUIRE PRESERVED THE GROUND/ON WHICH THIS MONUMENT STANDS. / CORNER STONE LAID, JULY 26TH, 1852 / WORK COMPLETED JULY 4, 1855. / SAMUEL SILLYMAN / FRANK HEWSON BUILDING COMMITTEE / EDWARD YARDLEY / MASTER MASON JACOB MADARA / STATUE OF IRON MOULDED AND CAST BY ROBERT WOOD. / COLUMN OF THE SAME MATERIALS BY / GEORGE B. FISSLER AND BROTHER. / THE STATE AND SECTIONS OF THE COLUMN WERE / RAISED TO THEIR RESPECTIVE PLACES BY / WATERS S. CHILLSON

— North face

HENRY CLAY / BORN HANOVER COUNTY VIRGINIA / APRIL 12, 1777 / DIED IN WASHINGTON, D.C / JUNE 29, 1852 / RESTORED BY THE PEOPLE OF SCHUYLKILL COUNTY UNDER THE / LEADERSHIP OF THE HENRY CLAY / MONUMENT COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN / STEVEN COTLER & JOHN C. BREYDENT / WORK BEGAN 1983. / REDEDICATED OCTOBER 19, 1985.

— South face

History

Background

Henry Clay was a Virginia-born politician who was active during the first half of the 19th century.[16] As a member of the United States Congress, Clay was a proponent of the American System, an economic plan that relied on high tariffs in order to foster the growth of American industry.[10] This especially applied to iron products produced in the United Kingdom,[2] which helped spur the development of the domestic iron industry.[16] Because coal is used in the production of iron products,[2] the tariffs and Clay's advocacy for it was well received in Pennsylvania, as it benefitted the state's anthracite coal industry.[3] This was especially true in the city of Pottsville, which was located in Pennsylvania's Coal Region and was a center of anthracite-mining.[18][19] Clay died on July 29, 1852,[20] and in Pennsylvania, he was memorialized as the namesake of a coal mine near Shamokin, and with the naming of the borough of Ashland, which is the name of Clay's estate in Kentucky.[7][21]

Plans for a monument

When he died, [citizens of the county] felt that because he was such a great statesman every state in the Union would erect a monument to him and they wanted to be the first.

Leo L. Ward, president of the Schuylkill County Historical Society, 1985[10]

Due to his economic policies that helped the anthracite industry, Clay was beloved in Pottsville, and within a month of his death, local residents were planning to construct a monument in his honor.[16] The Henry Clay Monument Association was established,[20] made up of several notable residents of Pottsville, including Frank Hewson, a civil engineer who worked on the Mount Carbon Railroad; Samuel Sillyman,[note 2] a coal mine operator and treasurer of Pottsville who was active in the Whig Party; and Edward Yardley, a businessman who operated a hardware business and served as president of a local natural gas company.[10] One of the first plans this committee developed was to hold a funeral procession for Clay in Pottsville.[10] On July 26,[note 3] 1,600 people attended this ceremony.[10] During these obsequies, a cornerstone for a monument to Clay was laid on land that had been donated by John Bannan,[note 4] a local Whig activist and publisher of the Miner's Journal.[20][10] The location for the monument was situated on a ridge below Bannan's Cloud Home estate.[17]

Builders

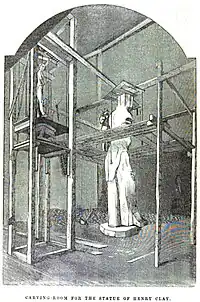

Following the placement of this cornerstone, work on the monument progressed slowly.[20] On August 16, the monument association established a building committee to oversee the construction of the memorial.[20] Hewson served as the project's architect and designed the overall design for the column.[10][8][4] This column was created by George B. Fissler.[23] Meanwhile, the statue of Clay was designed by H. Wesche, a Philadelphia-based sculptor,[2] and was cast at the foundry of Robert Wood & Company, also based in Philadelphia.[11][4][1] The statue would be the first monumental cast iron sculpture created in the United States.[3][9] In total, about 150 wooden patterns were used in the sand casting process.[24] Jacob Madara,[note 5] a local stonemason, oversaw the structure's stonework construction.[25][23]

Funding and completion

By November 27, construction of the base for the monument was completed, but work on the rest of the project stalled until 1854 due primarily to a lack of sufficient funding.[10] In total, the monument cost $7,151 (equivalent to $207,966 in 2021),[2] with a total project cost of $7,342.58 ($213,538 in 2021).[26][note 6] Of this amount, Sillyman provided approximately $3,000 ($87,246 in 2021),[10] the most of any single funder of the project.[27] The statue itself cost the monument association $2,090 ($60,782 in 2021).[9] On September 26, 1854, the first section of the column was received at Port Carbon and hauled to Pottsville, with more parts coming in the following months.[28]

On June 9, 1855, the monument association held a meeting to discuss further fundraising efforts and to plan a dedication ceremony for the monument, which they expected to hold that Independence Day, July 4.[29] Around this time, the association still needed to raise $2,433 ($70,757 in 2021) to complete the project.[10] By June 14, work on the column was fully completed,[10] and on June 23, it was hauled up the hill and to the base of the monument by a team of 12 mules.[2][8] Several days later, on June 26,[note 7] the statue of Clay was lifted atop the now-erect column by Walter Chillson.[30][note 8] An 82-foot (25 m) derrick was used in placing this statue.[9] The placement of the statue was met with cheers and a cannon blast from a crowd of sightseers that had gathered around the site.[30] Initially, the statue faced east, but one day after it was raised, it was rotated to face north, as the monument association believed that this position, which would allow Clay to overlook the city of Pottsville, was more appealing.[9] With the monument's completion, it became the first monument to Henry Clay erected in the United States.[27]

The monument was dedicated on July 4, 1855.[10][17][31][11][note 9] The dedication included a large procession that featured members of the local Independent Order of Odd Fellows lodge, veterans from the Mexican–American War, and members of various civic organizations.[32][33] The ceremony at the monument following the procession was overseen by Bannan and included speeches from several noted local citizens, a prayer held by a local priest, and the reading of the United States Declaration of Independence.[33]

Later history

By the mid-20th century, the monument had been more-or-less neglected and fallen into a state of neglect, prompting the creation of a new monument committee in 1953 to oversee preservation efforts.[10] Despite beliefs by the original constructors of the monument that theirs would be the first in a series of Clay monuments erected across the country, by 1985, the only other monument to the politician was at his gravesite in Lexington, Kentucky.[10] This is due in part to the fact that while Clay was well known during his lifetime, he had become a generally forgotten figure to the general public over the next century.[2] During the later half of the century, the area surrounding the monument was cleaned and the structure itself was refurbished.[10][16] In the 1980s, the statue was removed from the column for cleaning, and it was returned on August 26, 1985, and rededicated on October 19 of that year.[10] In 1994, the monument was surveyed as part of the Save Outdoor Sculpture! project.[11] By 2022, instances of vandalism to the monument prompted the installation of lights to illuminate the structure.[16] Around this same time, the monument faced possible structural issues due to erosion at the site, as well as the structure being partially obscured by surrounding trees, though Pottsville Mayor Dave Clews stated that preservation work on the monument was not a high priority to the city.[16]

See also

- Lexington Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places as "Lexington Cemetery and Henry Clay Monument"

- Statue of Henry Clay (U.S. Capitol)

Notes

- ↑ These dimensions are given by the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System.[11] However, different sources give conflicting values for the heights associated with the monuments. While many references agree that the statue is approximately 15 feet (4.6 m) tall,[2][4][12][13][9] the monument's entry in the SAH Archipedia by the Society of Architectural Historians states that the statue is approximately 2 stories tall.[1] That same entry states that the column is roughly 175 feet (53 m) tall.[1] Additionally, an 1853 article in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion states that the column is 63.25 feet (19.28 m) tall,[4] while a 2004 book by Anthony F. C. Wallace gives the height as about 50 feet (15 m).[13] Wallace also stated that the total height of the entire monument is roughly 66 feet (20 m),[5][14] which is close the value of 63 feet (19 m) given in a 2019 article by WFMZ-TV.[2] However, a 1924 guide book of Pennsylvania states that the height of the entire monument is 205 feet (62 m).[3]

- ↑ Alternatively spelled Silliman.[20]

- ↑ Multiple references state that work on the monument commenced with the cornerstone-laying on July 26, 1852.[20][10][22] However, a 2009 historical book by Pamela C. MacArthur states that the monument was "erected on 28 July 1852".[17]

- ↑ Alternatively spelled Bannon,[17] also given as Benjamin Bannan.[2]

- ↑ Also given as John Madara.[11]

- ↑ For a breakdown of the full costs associated with the project, as provided by the monument association, see Elssler 1910.[26]

- ↑ A 2019 article by WFMZ-TV states that the statue was raised atop the column on June 23, 1855.[2]

- ↑ Also spelled Chisholm.[2]

- ↑ Although multiple sources state that the monument was dedicated on July 4, 1855,[10][17][31][11] a 2004 book by Anthony F. C. Wallace states that the monument was dedicated on July 4, 1856.[13] Additionally, a 2019 article from WFMZ-TV states that an official dedication for the monument did not occur until July 4, 1885.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 WFMZ-TV 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Archambault 1924, p. 423.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion 1853, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Wallace 2003, p. 142.

- ↑ McDowell & Meyer 1994, p. 77.

- 1 2 Wallace 2004, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elssler 1910, p. 410.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Elssler 1910, p. 411.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 The Morning Call 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Smithsonian Institution Research Information System.

- ↑ Godey's Lady's Book 1853, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Wallace 2004, p. 168.

- ↑ Wallace 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ Yoder 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Keely 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 MacArthur 2009, p. 87.

- ↑ Taintor Brothers & Co. 1887, p. 106.

- ↑ Elssler 1910, pp. 406–407.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Elssler 1910, p. 407.

- ↑ J. H. Beers & Company 1916, p. 124.

- ↑ Good Intent Fire Co. No. 1 1899, p. 15.

- 1 2 Elssler 1910, p. 409.

- ↑ Grissom 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ J. H. Beers & Company 1916, p. 526.

- 1 2 Elssler 1910, p. 417.

- 1 2 J. H. Beers & Company 1916, p. 122.

- ↑ Elssler 1910, pp. 415–417.

- ↑ Elssler 1910, pp. 407–408.

- 1 2 Elssler 1910, pp. 410–411.

- 1 2 Elssler 1910, p. 412.

- ↑ Wallace 2004, pp. 173–174.

- 1 2 Elssler 1910, pp. 412–415.

Sources

- Archambault, A. Margaretta, ed. (1924). A Guide Book of Art, Architecture, and Historic Interests in Pennsylvania (Illustrated ed.). Philadelphia: John C. Winston Company.

- Elssler, Ermina (1910). "The History of the Henry Clay Monument". Publications of the Historical Society of Schuylkill County. Vol. II. Historical County of Schuylkill County. Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Daily Republican Print. pp. 404–417.

- "Monument to Henry Clay". Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion. Boston. IV (2): 32. January 8, 1853.

- "A Day at the Ornamental Ironworks of Robert Wood". Godey's Lady's Book (XI): 5–12. July 1853.

- History of the Good Intent Fire Co. No.1, Pottsville, Pa. Good Intent Fire Co. No. 1. Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Daily Republican Book Rooms. 1899.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Grissom, Carol A. (2009). Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850–1950. Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-031-7.

- Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania: Genealogy—Family History—biography; Containing Historical Sketches of Old Families and of Representative and Prominent Citizens, Past and Present. Vol. I (Illustrated ed.). Chicago: J. H. Beers & Company. 1916.

- Keely, Marshall (July 5, 2022). "Erosion, vandalism at Pottsville landmark". WNEP-TV. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- MacArthur, Pamela C. (2009). The Genteel John O'Hara. Bern: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03910-515-1.

- McDowell, Peggy; Meyer, Richard E. (1994). The Revival Styles in American Memorial Art. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-634-8.

- "Pottsville Statue Has Feet of Clay – And Remainder of Statesman's Likeness Spotlight". The Morning Call. October 2, 2021 [June 30, 1988]. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- "Henry Clay Monument, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Archived from the original on September 18, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- Taintor's Philadelphia and Reading Railway Guide Book. New York City: Taintor Brothers & Co. 1887.

- Thomas, George E. (July 17, 2018). "Henry Clay Monument". SAH Archipedia. Society of Architectural Historians. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. (2003) [1982]. The Social Context of Innovation: Bureaucrats, Families, and Heroes in the Early Industrial Revolution, As Foreseen in Bacon's New Atlantis (First Nebraska paperback ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9837-8.

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. (2004). Grumet, Robert S. (ed.). Modernity & Mind: Essays on Culture Change. Vol. 2. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9839-2.

- "History's Headlines: Henry Clay, The Great Compromiser, is remembered today by a Pottsville landmark". WFMZ-TV. October 9, 2019 [February 5, 2013]. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Yoder, Alexis (March 4, 2020). "24 Best Things to Do in Schuylkill County, PA in 24 Hours". College Magazine. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

Further reading

- Devlin, Ron (October 8, 2022). "History Book: Pottsville's unlikely love affair with Henry Clay". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Lee, Christine (July 5, 2022) [July 4, 2022]. "Resident, business owner notice more vandalism, erosion at Henry Clay monument in Pottsville". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- O'Grady, Gabriella (August 18, 2014). "Henry Clay monument to be revamped". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Pytak, Stephen J. (August 19, 2015). "Pottsville plans lighting at Clay monument". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- Pytak, Stephen J. (April 15, 2020) [July 3, 2013]. "Pottsville celebrates anniversary of Henry Clay Monument with commitment to maintenance". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on September 18, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- Pytak, Stephen J. (September 18, 2023) [August 29, 2014]. "Pottsville officials visit Henry Clay monument, discuss maintenance". Republican Herald. Archived from the original on September 18, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2020.