| Giurgiu Clocktower | |

|---|---|

| Native name Romanian: Turnul Ceasornicului din Giurgiu | |

| Yergöğü Saat Külesi | |

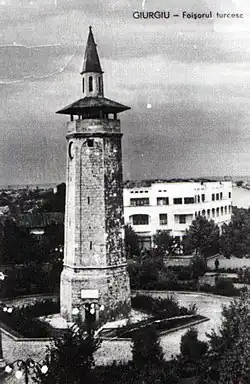

Historic Image of Giurgiu Clocktower | |

| Location | Giurgiu County, Romania |

| Nearest city | Giurgiu |

| Coordinates | 43°54′03″N 25°58′26″E / 43.90083°N 25.97389°E |

| Built | 1771 |

| Built for | Ottoman Military |

| Original use | Military Watchtower |

| Restored | 2007 |

| Current use | Clocktower |

| Architectural style(s) | Ottoman Architecture |

| Governing body | Ministry of Culture and National Patrimony (Romania) |

| Type | Architectural Monument of National Interest |

| Designated | 2004 |

| Part of | National Register of Historic Monuments (Romanian: Lista Monumentelor Istorice (LMI)) |

| Reference no. | GR-II-m-A-14913 |

Giurgiu Clocktower | |

The Giurgiu Clocktower (Romanian: Turnul Ceasornicului; Turkish: Yergöğü Saat Külesi) is a Historic Monument located in the City of Giurgiu, Romania. It has been designated by the Romanian Ministry of Culture and National Patrimony as monument of national importance. The city of Girgiu is located on the Danube river near the Bulgarian border. The city's location on the river made it a strategic asset for the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans started construction of the tower in 1770 and completed construction in 1771. Its initial purpose was to function as a military watchtower used for surveillance over the city and the river. It was later used as a lookout for fire prevention, similar to the guet royal and guet bourgeois ("burgess watch") established in France, which lasted until the 18th century.[1] After the Ottoman Empire lost control of the area, the tower underwent several modifications becoming what is known today as the Giurgiu Clocktower.

The monument is the symbol of the City of Giurgiu as well as a symbol of Giurgiu County, located on the official county emblem.

Watchtower

The Ottomans began construction on the tower in 1770, in the era of Russo-Austro-Turkish wars. Unfortunately there is no founding document to officially attest to its construction. It was built with the plans of an unknown European engineer, according to the military style of the era. Over the years, there has been local speculation that the tower might have been built by the Genovese founders of the city, others have speculated that its original purpose was as a minaret and part of a mosque complex. Researchers at the Teohari Antonescu Archeological Museum have debunked these speculations as false, with documentary evidence that the tower's purpose was meant to help the Ottoman Empire have proper surveillance and patrol capabilities of the Danube river.[2]

Likewise, similar towers were built in cities in Bulgaria, Albania, and Serbia. The majority of those were destroyed: either demolished by the locals or ruined during the independence wars of those nations against the Ottoman Empire.[3]

This particular watchtower was built in a slightly inclined position at a height of 22 meters, aspects that make it unique in south-east of Europe. It was also used as an observation point for the military during the Austro-Russian-Turkish wars. It remained the tallest building in the city until the communist era, when an apartment building was built which surpassed it in height.[3]

Watchtower to clocktower

After the Ottoman Empire retreated from Romanian territory, the watchtower underwent several modifications. In the 19th century and after 1830, a clock was added to the tower eventually creating the present tower. Its architecture was modified several times, especially in an attempt to repair various damage produced by the constant wars of the 19th century. Modifications began in 1830 and continued up to the First World War. During World War I, a large portion of Giurgiu was destroyed by a fire, including the upper floors of the tower.[3][4]

The clock's mechanism was replaced several times, with the original mechanism being discovered in 2005, which can be found at the Teohari Antonescu History Museum in Giurgiu. An interesting aspect regarding the tower is its hexagonal plan that surrounds the base which, in the 19th century served as a home to municipal firefighters, police, and City Hall. Teohari Antonescu Museum curator, Mircea Alexa, talks about the roles of the tower before the year 1906, stating “Principally, the firemen were hosted in the rooms of the tallest building in the city.” He continues, mentioned the period after the tower became a clocktower: “When the clock was put in place, part of the tower was cut to make room for the clock and the mechanism. Initially, the clock worked as a bell-- a town hall official pulled the bell to rally municipal meetings, this providing a very important municipal function.” [2]

As Giurgiu expanded and developed, city urban plans included the Clocktower as the central point of the city. Emil Paunescu, the director of the Teohari Antonescu Museum in Giurgiu, explains that the first inclusion of the tower in urban development was done by Austrian engineer Morris Van Ott in the official city plans. Paunescu goes on to say that “the earliest plan is from 1832 and encompasses the same concept as that found in the city Braila, which also had the same author for that city's urban plan. Another urban planning characteristic is that in its center there was once a circular area that locals called The Saucer (farfuria cu tei) due to its round shape. This was the historic location of the city’s main promenade.” [3][4]

After Romania entered World War I in 1916, Giurgiu was mostly destroyed. Bucharest and the southern part of Romania were occupied. The Germans had the command, but the majority of those stationed in the vicinity and in Giurgiu were Bulgarians. The troops were extremely violent, retaliating on the locals of Giurgiu for their role in the Balkan War which saw the occupation of Cadrilater. The Bulgarian troops encountered no resistance and there was no street fighting. However, after the troops entered the city, they set fire to the town and the tower, killing most of the people in their path. As a result, in 1918 when the Bulgarians left, more than half of Giurgiu was razed.[5]

The tower was subsequently renovated, only to be left without a roof again in 1932. After the economic crisis was over, the renovation was entrusted to the architect Horia Teodoru which completed another renovation in 1934. However, during this renovation, the building surrounding the base of the tower was however not rebuilt.[2]

After the Romanian Revolution, representatives of the “Teohari Antonescu” Museum requested from the local authorities the permission to assess and examine the tower. The assessment was completed in 1996. A new series of renovations began in 2001 and ended in 2007. The focus of this last renovation was consolidating the foundation of the tower, strengthening the structure by reinforcing it with concrete and, yet again, rebuilding the upper part of the tower.[3]

Legend of the tunnels

Local legends purport that there are several tunnels beneath the clocktower.[6] These tunnels were said to have started at the base of the tower and continue to the old fortified walls of the city. Inspired by these legends, researchers and archeologists from the local community were interested in excavating around the tower. Researcher Mircea Alexa talks about how they wanted to verify these legends and took advantage of the renovations in the early 2000s as an opportunity for their discovery. Thus, they obtained an approval to dig around the tower, at its base. Colonel Dan Capatana, an archeologist and the former head of department at the Military Museum was also there during the excavation. The legends were debunked during the 2001-2007 renovation and restoration of the tower as no tunnels were discovered.[2][6]

The initial disappointment quickly dissipated when workers stumbled across the clock's original mechanism in 2005. Workers initially planned on discarding the mechanism thinking it was rubbish. After a closer look, local researchers assessed it to be the original mechanism of the clocktower. The gong alone weighed more than 50 kg.[3]

Influence on local architecture

The clocktower influenced the layout of modern Giurgiu by urban planners into a star shaped organizational layout, drawing inspiration from Paris. The “étoile” system was introduced around the year 1877 as the city expanded. The clocktower was considered the center of the star and all main streets have their starting point at the tower's promenade and extend to the rest of the city, creating the star shape. The first area surrounding the tower was known as Carol I Square, renamed to Carol II Square, and currently Unification Square which includes the promenade. The squares were surrounded by parking for vehicles and the promenade was lined with shops.[2]

Each arm of the "star" layout was a principal neighborhoods, identified in municipal plans by specific colors. Therefore, each arm of the city was a different color on city schemata. According to historic urban plans, there were five colors: red, yellow, blue, green, and black. The black color, for instance, corresponded to the old village Smarda, which is now a part of the city, while green was for a neighborhood where both Romanians and Bulgarians lived.[3]

After 1960, the communist regime slowly destroyed the historic urban planner's vision for the city and its star layout by building soviet-style apartment blocks throughout Giurgiu. The communist government planned to build apartment blocks to form a rectangle around the tower and even considered physically relocating the clocktower. These were never realized. However, a soviet-style apartment block from the communist period named “Eva” became the new tallest construction in the City of Giurgiu.[3]

Today, the tower is a local tourist attraction and can be visited any time. The main area around the tower was rebuilt according to the historic plans. The space surrounding the tower was leased and many coffee shops and restaurants were built there. Locals consider the rebuilt area as kitsch and lacking the beauty of the old square. They believe that modern buildings with shops and restaurants should not have been built near the historical monument. After a number of protests by local citizens in the 2000s, the square surrounding the tower was not extended any further.[2]

References

- ↑ Nicolae, Adrian (July 2011). "THE FLUVIAL LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVE BETWEEN GIURGIU AND CALARAȘI WITH CULTURAL IDENTITY INSERTS". Editura Presa Universitara Clujeana. July 2011 (University of Bucharest, Faculty of Geography). Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Roman, Geta. "Turnul Ceasornicului din Giurgiu, locul de unde s-a scris istoria "orașului-stea"". Historia. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dumitru, Andra Mitia (February 10, 2014). "Turnul Ceasornicului din Giurgiu". Giurgiuveanul. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- 1 2 Bigan, Camelia (November 21, 2014). "Turnul Ceasornicului şi Cetatea lui Mircea cel Bătrân, monumente emblematice pentru municipiul Giurgiu". DESTINAŢIE: ROMÂNIA. AGERPRES. Agerpres: Romanian National News Agency. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ↑ "GIURGIU ÎN PRIMUL RĂZBOI MONDIAL". MuzeulGiurgiu. Giurgiu County Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- 1 2 Iederă, Felicia. "Legenda Turnului Ceasornicului din Giurgiu pe care mulți nu o cunosc". Secretele. Retrieved 13 May 2019.