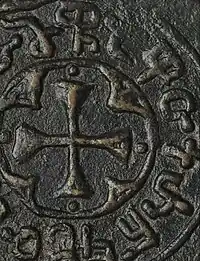

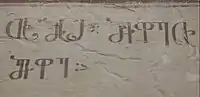

Mepe (Old Georgian: ႫႴ;[lower-alpha 1] Georgian: მეფე [mepʰe]; meh-PEH) is a royal[4] title used to designate the Georgian monarch, whether it is referring to a king or a queen regnant.[5][6] The title was originally a male ruling title.[7]

Etymology

The word is derived from Georgian word მეუფე (meupe)[8] which literally means sovereign and lord.[9][10] Some Georgian dialects has the term as ნეფე (nepe), all derived from common Proto-Kartvelian მფ/მეფე/მაფა (mp/mepe/mapa).[11] Even though mepe has a female equivalent, დედოფალი (dedopali; lit. 'queen')[12] it is only applied to the king's consort and does not have a meaning of a ruling monarch.[13]

History

The term mepe was utilized since pre-Christian beginnings with Azo, but the role would get more structured during the reign of Pharnavaz I[14] in the 3rd century BC.[15] His successors, the Pharnavazid[lower-alpha 2] mepes would be titled as goliath[19] who would possess 𐬓𐬀𐬭𐬆𐬥𐬀𐬵 (pharnah; lit. 'royal radiance'),[20] the divinely endowed glory believed by ancient Persians[lower-alpha 2] to mark only a legitimate ruler.[21] Georgian monarch's reign was known as მეფობაჲ (mepobay; lit. 'kingship').[22][23]

In the late 6th century, the Sassanid Empire would abolish[lower-alpha 3] the Georgian kingship of the Kingdom of Iberia resulting in the interregnum stretching from c. 580[lower-alpha 3] to 888 as a demoted principality.[27][28] Despite the monarchy was in abeyance, and that royal governing disintegrated, the principality rulers would still continue to claim to be referred to as mepes and ჴელმწიფე (helmts'ipe; lit. 'sovereign').[29] After 888[30][31] (or 889)[32] restoration under next successive dynasty[lower-alpha 4] of mepe Adarnase IV, the new kingdom would emerge as the fusion of many lands and territories, that would lead towards a total Georgian unification, culminating in 1008.[33]

In the 12th century,[34] the Bagratid[lower-alpha 4] mepe David IV the Builder, who had established himself as the region's superlative political and military force,[40] with his ambitious and sophisticated push for his kingdom's royal imagery promotion,[41] the official style of a king would become imperial[42] თჳთმპყრობელი (tuitmp'q'robeli lit. 'absolute master')[43] and მეფეთ[ა]მეფე (mepet[a]mepe;[44][45][lower-alpha 5] lit. 'King of Kings'), similar to the Byzantine βασιλεὺς βασιλέων (basileus basileōn) and Persian شاهنشاه (shahanshah).[50] David IV's royal projection of his grandiose title was partly aimed at a non-Georgian audience.[51] Title Shahanshah was later totally usurped[52] and consistently used by Georgian monarchs, denoting sovereignty over several Persianate subjects such as Shirvanshahs, the Shaddadids and the Eldiguzids.[53] The royal cult of a monarch would reach its zenith with a female ruler, Tamar, whose execution of power would inaugurate the Georgian Golden Age, her being styled as Tamar, the mepe.[54] Tamar was given the longest and more elaborate titles on the royal charters, listing all the peoples and lands that she ruled as a semi-saint mepetamepe.[55] The Bagrationi mepe, with its royal legitimacy and ideological pillar, would rule Georgia for a millennium, from its medieval elevation down to the Russian conquest in the early 19th century.[56]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 The terms ႫႴ (mp), ႫႴႤ (mpe) and ႫႤႴႤ (mepe) were used simultaneously. Such abbreviations were common in Georgian.[3]

- 1 2 The Pharnavazids were fascinated by the Persian structure of royal administration, yet cultivated close relations with the Hellenistic Seleucids.[16] The pre-Christian Georgian kings modeled themselves in a same heroic garb as in the Iranian epic cycle and imagery,[17] also incorporating several allusions to the Hebrew Bible and Classical Syriac sources.[18]

- 1 2 The Chosroids were dethroned immediately after the death of King Bakur III.[24] Bakur's sons would remain in the mountainous region of Kakheti;[25] their royal pedigree would rule the region as titular princes styled as mtavari.[26]

- 1 2 The Bagratids restored the royal authority soon after they succeeded the Chosroids and seized the Principality of Iberia in 813.[35] They brought rapid expansion and consolidation within Georgian polities. Bagrationi monarchs would base much of their culture modeling and competing intensely with the Byzantine emperors.[36] They frequently claimed saintly status and linked themselves with the divine, eucharistic symbolism, had Davidic lineage pretensions,[37] their royal superiority always depicted haloes and crowns and surrounded by the warrior saints.[38] 12th century icon preserved in the collection of the Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai shows King David IV, styled as "pious emperor", standing next to Saint George and receiving the crown from Jesus Christ.[39]

- ↑ The first Georgian king to assume the title "mepet[a]mepe" was Gurgen of Iberia,[46] but the term would become absolute and universal during and after David IV.[47][48] Gurgen's title is elaborated by the Bagratid-commissioned chronicler Sumbat Davitis Dze, explaining Gurgen being a mepe, and a father, of another mepe. Gurgen ruled the Kingdom of the Iberians, while his son, Bagrat, led the Kingdom of the Abkhazians.[49]

References

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 58

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 182

- ↑ Rapp, p. 38

- ↑ Rapp, p. 472

- ↑ Rayfield, location: 1292

- ↑ Rapp, p. 263

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 178

- ↑ Klimov, p. 120

- ↑ Rapp, p. 265

- ↑ Klimov, p. 196

- ↑ Klimov, pp. 195-215

- ↑ Rapp, p. 286

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 109

- ↑ Rapp, p. 182

- ↑ Rapp, p. 153

- ↑ Rapp, pp. 11-277

- ↑ Rapp, p. 154

- ↑ Rapp, p. 141

- ↑ Rapp, p. 155

- ↑ Rapp, p. 205

- ↑ Rapp, p. 276

- ↑ Rapp, p. 261

- ↑ Bakhtadze, pp. 1-4

- ↑ Rayfield, location: 980

- ↑ Rapp, p. 426

- ↑ Rapp, pp. 233-471

- ↑ Rapp, pp. 372-451

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 5-6

- ↑ Bakhtadze, p. 3

- ↑ Rayfield, location: 1337

- ↑ Rapp, p. 337

- ↑ Bakhtadze, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Rapp, p. 231

- ↑ Rapp, p. 187

- ↑ Rapp, pp. 165-231-479

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 5

- ↑ Rapp, p. 370

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 118-121-201

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 69

- ↑ Rapp, p. 338

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 70-71

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Rapp, p. 396

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 134

- ↑ Rayfield, location: 2194

- ↑ Bakhtadze, p. 29

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 39

- ↑ Rapp, p. 501

- ↑ Bakhtadze, pp. 20-22

- ↑ Rapp, p. 372

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 67-70

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 92

- ↑ Rayfield, location: 2199

- ↑ Eastmond, p. 97

- ↑ Eastmond, pp. 162-178

- ↑ Rapp, pp. 234-338

Bibliography

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003) Studies In Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts And Eurasian Contexts; Peeters Bvba ISBN 90-429-1318-5

- Eastmond, A. (1998) Royal imagery in medieval Georgia, Pennsylvania State University, ISBN 0-271-01628-0

- Rayfield, D. (2013) Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, Reaktion Books, ISBN 9781780230702

- Bakhtadze, M. (2015) Georgian titulature of Tao-Klarjeti ruling Bagrationi dynasty, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Institute of Georgian History Proceedings, IX, Tbilisi, Publishing Meridiani

- Klimov, G. (1998) Etymological Dictionary of the Kartvelian Languages; Walter de Gruyter GmbH; ISBN 9783110156584